by Pauline Valade

Climbing began as my deepest wound and became my greatest remedy—a journey where the poison and the antidote were the same.

Like a lot of the nonmale climbers in my community, I started climbing with a man: My first partner. And the most traumatic experience I’ve ever had in a relationship. Quick backstory: I grew up in a broken family. My mom ran away from my narcissistic father when I was 10, leaving me alone with him and the beginning of a long nightmare. If you know me, you probably think I’m one of the bubbliest people you’ve ever met. But I have become this way because I have walked through many dark places in my mind. Growing up from a traumatized childhood, my first romantic relationship was pure chaos—self-destructive and toxic.

I started bouldering with this man I found myself dating just to impress him. He called me “lazy,” “non sporty,” and “mentally weak”. But I kept going, even after the breakup, even after I realized how wrong it all was…Until my first big injury.

The date: December 2019, Time: Late Sunday, setting: indoors at a climbing gym. There I am, hungover, two hours battling with a V4. I pushed, I fell – pop! My meniscus and ACL were so damaged I couldn’t maintain this weird addiction I found myself caught up in. The Covid crisis was right around the corner. France was on lockdown, even hospitals closed their doors to everything but the crisis. My world collapsed, and I finally had time to process just how abusive that relationship had been.

No climbing. No school campus. No family visits. No medical care. I was stuck at home for 18 months, watching the world shrink. Politics sucked. Then, another breakup. With someone I truly loved and deeply appreciated—someone who mattered. But in the end, the reasons made it clear that we weren’t meant to be together. This story isn’t about him, though he played a part in helping me heal. He’s still important to me and I hold a lot of tenderness for him.

Time is tough. I need a change of air—I’m suffocating.

Fast forward two years, I finished my master’s in food sciences and agricultural engineering, I built stronger friendships, and I found myself again. My new friends made me feel seen and loved. I healed partially, started therapy, and had two surgeries that resulted in three rounds of physical therapy. I did it alone, but not really. I had friends who showed up and supported me and reminded me that I wasn’t just surviving, I was rebuilding and they cared.

My college friendships allowed me to immerse myself in a community for the first time. STEM students in environmental sciences are the best people to hang with. For me, these were and are my people for life. And back then, I thought I’d never experience that feeling again.

Now we’ve all graduated. Some moved away, some returned home, and others ventured abroad. And me? I’m craving distance—far from my country, far from my trauma. Fueled by the love and support of my friends, my brother, and my uncle—the only healthy male role models in my life (if my brother reads this, he’ll definitely laugh)—they are the kind of men who make you believe in men. Connected to their femininity, they’ve always been my blueprint, the ones I’ve looked up to, hoping to grow like them, to experience the adventures they chase.

And now, here I am, sitting on this plane, holding a one-way ticket. I only cried once—when I turned back and saw my grandpa through the airport customs, his eyes welling up. He knows this might be the last time we see each other. Though, knowing him, he’ll probably outlast all of us.

I’m not afraid, just excited. Deep down, I know this is going to be life-changing. But at the time, I had not expected this much change. I left France with my mom’s clumsy farewell: “You’re gonna find an American boy and never come back.”. And she’s right—I’m not coming back. But not because I found someone. Because I found myself, thanks to a community of women and the pursuit of the meaning of womanhood.

My first move after arriving in SF? Checking out the local climbing gyms. I found two in Santa Rosa. My host mentioned one called Session, a new gym opened by a well-known local climber. It looked great.

The next morning, I borrowed a bike, crossed those chaotic, definitely not bike-friendly American roads, and arrived. There I was, standing at the front desk, signing up for an annual membership, awkwardly asking about the grading system in my broken English.

And my fear.

All my social anxiety, my climbing trauma, and my French ego crashed together. I hadn’t climbed in two years. My first surgery left me with Cyclops syndrome, my leg muscle had shrunk by over a centimeter (.4 inch), and I hated how weak I felt.

To understand my mindset, you need some cultural context. Back home, machismo is everywhere—misogyny, too. I grew up a “tomboy”’ surrounded by male friends and my brothers, always the little ones in the group. I spent a lot of my time comparing myself to other women and viewing them as threats while also questioning my sexuality and identity. What if they’re stronger than me? Prettier than me? Fitter than me? Growing up French doesn’t help. We’re practically professionals in body shaming and self-comparison. If another girl seemed “out of shape” (by my messed-up standards), or shy, or less educated, she wasn’t a threat. (Yes, I know. Gross.)

So once again I was alone in the bouldering section at Session, struggling to send a V1, getting absolutely humbled. Young, French, arrogant—it was a rough session. My English sucked. I was lost in conversations, and nobody talked to me.

I know loneliness. I grew up with it. But I also knew I could make friends—I had done it before.

So I showed up. Again. And again. Because consistency is key.

Six months passed. Still no real friends. I didn’t have the cheat code yet. I was still too arrogant, trying too hard to be liked. But I kept showing up despite feeling left out and rejected and dealing with the flakiness, one of the many cultural shocks I had to face, amplified by the climbing community. But I still showed up over and over.

Then I realized—I wasn’t doing it for other people. I was doing it for low self-confidence, injured me. The little me. The me who always knew that if she didn’t show up for herself, who would? The me who had been humiliated by a father and a boyfriend.

And that’s when I met the people who truly mattered.

After an ankle sprain, I met one of my closest friends now. A strong climber. She didn’t ask where I was from—she asked what I was climbing. I never felt threatened by her, even though she was stronger than me, cooler than me. She coached kids, climbed with the boulder bros, earned their respect, and knew how to handle them. She just wanted to be friends. And now she’s one of my favorite contacts on my phone.

Siany pushed me hard. She made me cry a little bit but laughed with me more. She was the first woman who truly believed in my skills. And she introduced me to rope climbing. At first, I was terrified. I didn’t want to do more.

So I started hanging out with rope climbers. More women. More queer climbers. Different ages, different backgrounds. I gained confidence. I climbed with more people—especially more women. They hyped me up, and waited patiently while I worked on my projects.

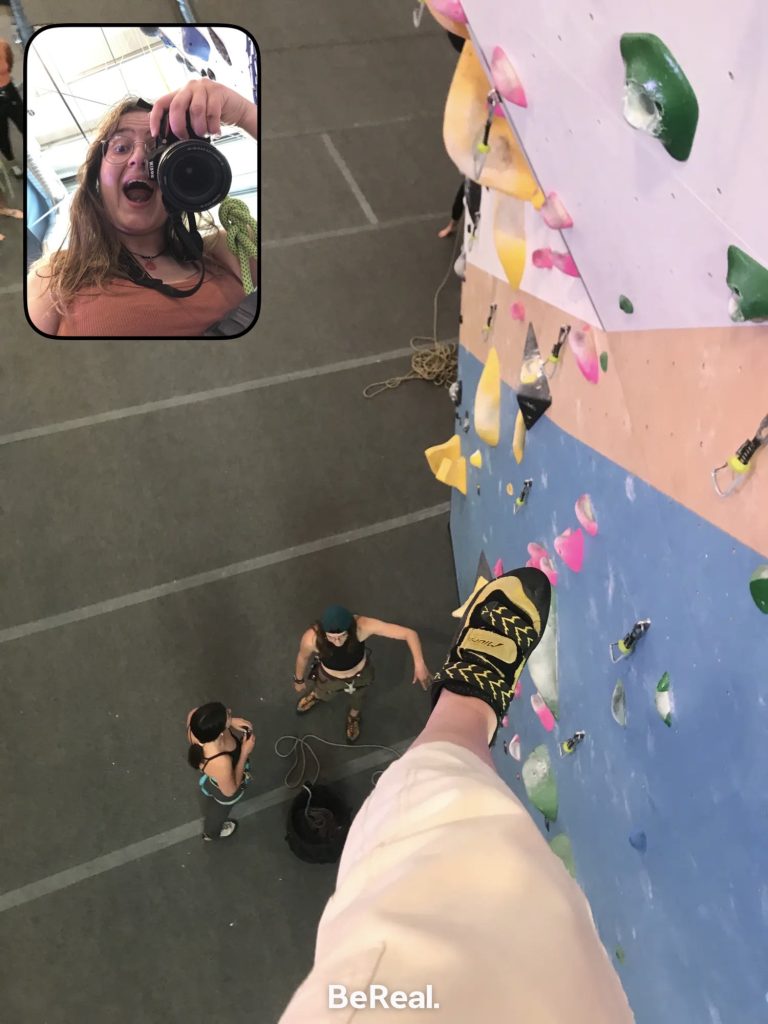

Then I got invited to take photos for the Women Lead Club during one of their first meet-ups. I felt like an imposter being there—surrounded by strong lead climbers. But it was the perfect excuse to talk to them, to connect. And for the first time, I really saw how many strong female climbers were out there. I observed them move through the routes, trying to get the best beta. I noticed how technical and precise they were. Footwork? Perfect. Body positioning? Calculated. The older the climber, the better the technique. It wasn’t about brute strength. It was about smart strength. It was a different world from the boulder bros (who, don’t worry, we still love).

That’s where I met another important hooman in my climbing journey. They are like me: loud, high-energy, and enjoy nerding about rocks and dogs all day long. They decided we were going to be friends before I even finished introducing myself. If I had to define climbing through one person, it would be them.

I hesitated for months before finally leading. My friends pushed me as the relationships between us developed. I trusted them with my life. They were the ones who took me on my first outdoor rope climb. And again, I was humbled. My most perfect days were climbing with my belay buddies and probably made me cry from my own fear, from feeling weak. But they never made me feel awkward about it. They welcomed my feelings. And they threatened me if I didn’t stop being so hard on myself. (In a good and productive way which is actually working)

Then my second biggest injury happened—a silly ski accident. My whole knee was compromised this time, and it was bad. I dropped a message in the WLC group chat, and everyone jumped in to help. A chiropractor guided me through the medical system and gave me solid advice. My friends took turns giving me rides everywhere—especially to the gym—making my self-PT so much easier.

I cried. A lot. In front of everyone. Even though my biggest fear was looking sad and vulnerable in front of people. And yet, I never felt awkward about it.

The Women’s Lead Club started to take over the workout area. Less manly. More female climbers hanging out there make the space feel safe.

One time, I had a bad interaction with an old white guy at the gym. Instead of brushing it off, blaming my bad English, or gaslighting myself into thinking it wasn’t a big deal, I dared to send a message about it in the group chat. Within minutes, I had at least ten responses—not just from the gym managers, but from the women in the club, some of whom didn’t even know me. Not one of them doubted me. They took action. They confronted him.

I wasn’t alone anymore. I had a gang of humans who had my back. They gave me the will to stay consistent with my PT.

I went back to France for visa issues and returned three months later. TERRIFIED. What if everyone forgot about me?

But for the second time that year, I was hit with a wave of love. The first was when I went back home. The second was when I came back to my new home.

Everyone wanted to pick me up at the airport. I landed on flowers. I cried. (Yes, I cry a lot.)

Any international knows—the first time you come back after visiting home is the hardest. You feel torn between your home country and the one you fell in love with. You’re just a freaking lost potato in the middle of a giant field. Nobody really relates. Nobody truly gets it.

But my community was there. They hadn’t forgotten me.

I started climbing again—still injured, still recovering after five months off. And I missed it so much. New faces started appearing in my life. Friendships I never saw coming.

Some of them will be with me for my first (bailed) multi-pitch experience in the Valley. (And guess what, dear Frenchie? Of course, there were tears.)

It was the first time I experienced real fear—the kind I created myself. I’ve felt unsafe most of my life, not feeling secure at home. That fear, I know. But this? This was different.

For that climb, I followed Rae. Like I said, they’re one of the only people I trust with my life. They know me by heart—my mental limits, my abilities. And here I am, broken, on a crack climb (a style I’ve never done), following “C.S. Concerto,” first pitch. Once at the end of the pitch, I did not fully grasp what just happened. I probably spent an hour on that wall. I felt myself shaking with fear, my knee is screaming, and I know we’ve lost too much time to finish before sunset.

But I made it.

I’m exhausted, my knee’s a mess, and I’m deeply disappointed in myself for needing to bail. But Rae—damn Rae—knows our limits. And if we’re here in Yosemite, it’s for their birthday. I’ll wait while they chase their pitch goal.

That’s what’s running through my head when my friend’s partner—already on the third pitch—asks over the walkie if I made it.

“YEAH, she freaking finished it!” my friend yelled, exulting, proud.

Two seconds of silence. Then, through the static:

“YEAHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH!”

It wasn’t fake. They weren’t cheering me on just to be nice. They meant it. They believed in me. Maybe even more than I did.

(And no, I won’t explain whether or not I cried. You know by now.)

From that spot, I looked around. I had never seen the Valley from this angle before. El Cap stood right there, massive and indifferent. I was in my favorite park in the world. With my friends. Safe. And life was beautiful.

It’s been 2.5 years since I moved to the States. And I can finally say: I have found a community. More than that—I’m part of it. I’m building it, alongside the extraordinary humans I’ve met at the climbing gym, through the Women’s Lead Club. Every time I falter, they are there. They make me feel safe and protected, even when my lifestyle pushes me out of my comfort zone daily.

I didn’t know what I was looking for until I found them.

And I know, deep down, that this is just the beginning of many beautiful stories.

This club didn’t just heal my wounds. It opened the door to womanhood for me. And I am terrified that some people live their entire lives without experiencing this. Because it is truly powerful.

While I was in France, I stayed with my grandpa—an 80-year-old man who has spent his life in the closet. He grew up in wartime Paris under bombings, raised by a strong single mother, and never once said I love you—an interesting man.

After a big fight—about the way he treated my older brother, who lives with him—I asked him why it was so hard for him to say those words. Why couldn’t he open up to us, especially when, for a long time, he was the only figure of love and understanding in our lives?

He knows I go to therapy—he’s the reason I started four years ago. And yet, his answer?

“Ça a toujours été facile pour toi, ces trucs-là.” (It’s always been easy for you, this kind of thing.)

I’ve thought about that sentence ever since. And I’ve realized—he’s wrong.

I never learned how to say it. The French are known for their romance, for their declarations of love—but we are also proud people, reserved when it comes to showing vulnerability.

And California? California taught me how to say it. The women who surround me taught me how to say it.

I wish I could visit my younger self and tell her: We love climbing. We are building our life around it. My relationship with my mom is still precarious, but now, I see her differently. And that’s because of the beautiful, strong women and mothers I have met in the WLC.

Womanhood did that.

And all those who fear its power? They have good reason to be afraid.

Leave a Reply