by Ally Shoemaker

Growing up, the last adjectives that someone would have used to describe me were strong, athletic, and extroverted. I was a relatively shy, academically inclined kid who had quite literally no meat to her bones and zero strength. I was described as ”petite,” when really I was a twig, weighing 68 lbs in 6th grade and only 95 lb when I graduated high school. This body type really didn’t lend itself well to much of anything athletics-wise. Looking at myself now, I’m both surprised and so thrilled with the turns that my life took that brought me to the capable, strong, and social woman I am today.

Throughout childhood, I constantly got praised for being good at school, although I struggled with competitive sports and things that required strength or coordination, such as snowboarding, swimming, or any sport that involved catching things. I also avoided things I was bad at like the plague, wholly uninterested in forcing myself to keep doing things that I didn’t get praise for or that made me feel unsuccessful.

In high school, the non-academic, non-athletic extracurricular that I felt safe in was theater. I find this ironic, because in theater you’re on display for an entire audience, especially in improvisational theater, which was the community I found myself in. Despite being a pretty quiet kid I thrived there, falling in love with my quirky improv group and with being on stage. This thriving I now understand came from feeling safe with the strong bonds I’d built with my improv “family.” Without them and the knowledge that they’d never compromise me on stage or put me in a position to do something I was bad at on stage, I’d have never been brave enough to perform in front of others. Unfortunately, when I went away to college, I didn’t have the confidence to try theater on a larger scale.I grew up in a pretty small town. I masked that and my fear of failure by saying that it wouldn’t be the same without the group I’d spent four years growing, playing, and bonding with.

To fill that community hole, I did something really out of pocket and joined a sorority. There I managed to find a few select humans I felt I could relate to. I didn’t even consider building a new theater community. I didn’t want to make myself vulnerable and potentially find out that I was only “good” at this thing in my small town because there was no one else to do it. No thank you. Let’s stick to this comfortable bubble where failure wasn’t even a part of the equation, let alone an option.

Partway through those college years, I started working as a gymnastics instructor for preschool age children up to 12 years of age and let me tell you, the imposter syndrome was REAL. I practiced gymnastics as a very small child, but I didn’t believe I had the ability to do the things I was teaching. I wasn’t athletic or coordinated, or at least that’s what I’d been telling myself for over a decade. Slowly, I started working on skills at an adult gym, learning I was more capable than I thought, but also seeing that I was not as capable as everyone I saw around me. I would only go to the adult gym if it was a slow evening so I could work on things without feeling the shame of being watched by the imposter syndrome rearing its head. What seemed like relatively simple skills were so difficult for me coordination and strength wise. I only continued to try because of pressure from my competitive gymnast partner, but every step of the way it was painful and disheartening to realize I’d been right all along: my body and brain just weren’t made for athletics.

Fast forward a few years, I moved to Sonoma County. I was leaving all the communities I’d built, known, and loved, once again, to start anew. To attempt to build community and my physical self, I did yet another out of pocket thing and joined a Crossfit gym. As I learned more and more ways to safely use and move my body and build strength, I watched my body and confidence grow in so many ways: I WAS athletic, and actually pretty strong for my size. The people around me saw it too.

The most stark example of this was the day a girl at my gym encouraged me to use a 35 pound dumbbell (literally ⅓ of my weight at the time) for a workout because she knew I could. Succumbing to peer pressure, I did it. I tried the workout with the heaviest, scariest dumbbell I’d ever touched. I didn’t finish the workout in the time limit, but I did get pretty darn close, and more importantly, I saw for the first time just how much I’d been holding myself back in my own narrative, about who I was or wasn’t as an athlete.

This newfound confidence and sense of self felt so good. I fully embraced it, competing a few times and loving every moment of proving to myself day after day that I was fit, capable, and pretty damn strong. I was stoked to be surrounded by powerful humans that were always supportive and encouraging, though I was forced to also recognize how hard it felt to become deeply connected with them. I wanted these people to be my people so badly, but I always felt a little misaligned and on the outside. Despite this nagging feeling that I didn’t totally fit in, Crossfit was my haven for six years.

Then in 2021, my whole world came crashing down in a matter of months – my job as a teacher had changed drastically, thanks to Covid and involuntarily being moved from 3rd to 6th grade, my grandfather that I’d been helping take care of died, my aunt passed away, and I exited a relationship I’d thought would end in marriage. In my grief, I felt lost and like I had no one. I questioned what community or people I had in this place I’d been calling home. I continually felt as though I was a burden in my ongoing loss and depression and no one wanted to hold space for me. With this came a huge surge of social anxiety and me second guessing every interaction with the people around me and feeling as though I needed too much, was too much, and that I clearly did not fit in and everyone knew it.

To try to escape and unwind from my grief and following anxiety, I turned to traveling and decided to spend my summer break of 2022 road tripping through the midwest. My thought was if I could just remove myself from the places I felt so disconnected to and numb, and yet so pained, maybe I’d finally be able to find some healing and peace.

Less than 48 hours after leaving home, I got a phone call that my grandmother had died. It felt unreal. At the urging of my grandfather and parents, I stayed in the midwest to continue with my plan and get the distance and grieving time I needed. Thank god I did. Two and a half weeks into the trip, I pulled into The Outpost, a campground next to the New River Gorge National Park in West Virginia. At the office desk sat Ben, a man who, in my week of staying there, would change my life and help get me on a path to healing.

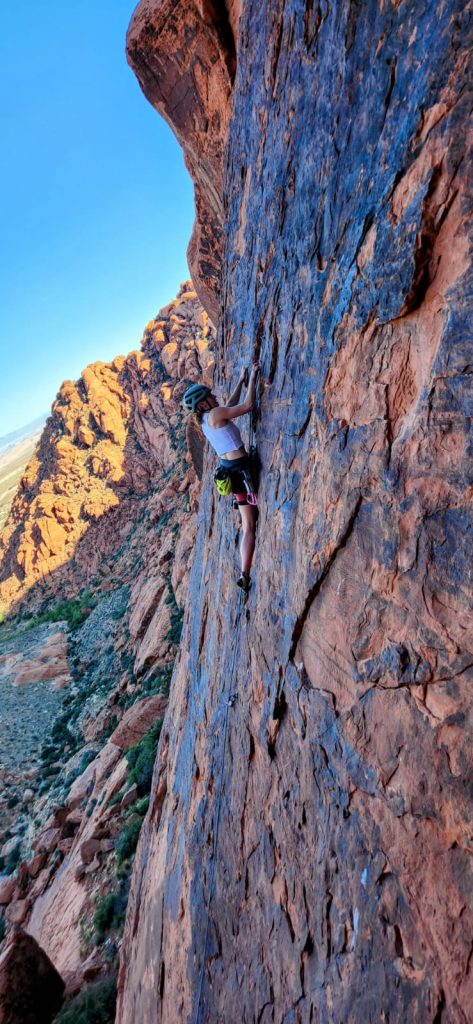

My traveling all over the US and the world for the prior 6 years had introduced me to so many humans and brought me to so many beautiful natural places. The New was not any more fantastic than the other places I’ve been, but it did have a remarkable climbing community. Ben took me and his sister out bouldering with his buddies, and I watched myself use this beautifully strong body I’d built with Crossfit, make its way with ease up rock faces, topping out on boulders that gave you stunning views of the forest in the gorge. That coordination I’d told myself I never had, seemed less of an issue because I’d spent years learning how to use my body and build it. Even the climbs I couldn’t send didn’t leave me with the same disheartened, self critical feelings and thoughts I’d had when trying athletic things previously. I wanted to go back and get the send. I wanted to prove to myself that I could persevere through challenging things with this body I’d built and apparently finally learned how to navigate.

As I scaled rock faces, connecting with the natural world in a whole new way, surrounded by forest and humans stoked on life, for the first time in over a year, I felt twinges of hope and I felt joy. The days I spent climbing in the woods of the New showed me there was a light at the end of this dark tunnel I’d been living in for over a year.

I went home and immediately joined Session, which had coincidentally just opened. Every day I went in excited to see what I could accomplish that day and excited for who I’d meet. This was in stark contrast to going to Crossfit, where I was feeling my social anxiety more and more; I felt burdensome to the people I knew well. I wasn’t doing well and it was easy to feign happiness in front of new people at the climbing gym, but not as easy to fake with those I had known for years. Each day at Session, I met a slough of new people, leaving most days with a new friend or two and getting much needed serotonin boosts from all of my interactions. I thought I’d start to feel better. I mean I loved climbing and I loved interacting with new people, surely together that would solve everything, right?

Then my other grandmother died, and with that an onslaught of family issues; The insurmountable grief I’d been trying to move through got heavier. I threw myself into climbing and exercising, an ultimate form of endorphin chasing, to feel anything but the overwhelming storm inside.

In this obsessive climbing state, I found “my group,” a hodgepodge of men and a few women who were full of life and energy, which I desperately needed. I hung with them at the gym until 10 at night, learned to lead climb, started going on climbing trips, and learned to multi pitch, all attempting to “fake it ‘til I made it” and not show how much I was hurting and subsequently feel like a burden to these new people. Climbing had given me a glimmer of hope, and I was full sending into it, clinging to the idea that it would fix things and crossing my fingers that I was right.

Unsurprisingly, it didn’t. A year into this pretend healing, I got sick, and through the process of trying to figure out why my body was revolting against me, I made a decision to take a leave of absence for an entire school year and focus on getting well, physically and emotionally. I thought, once again, that maybe if I just traveled and left Sonoma County, the place I felt so awful in, and if I spent a year focusing on myself and healing, that I’d feel better, that I’d be fixed.

It became clear that that was escapism and not a solution, so during my year off, between the most remarkable trips abroad, I came home and got real with myself. It became glaringly obvious that what I was really missing was a sense of my worth and a sense of my value in the community spaces I found myself in; I’d felt so lost and so burdensome to others, like the people around me weren’t actually my community and didn’t want to show up for me in these months of darkness. I didn’t trust that they valued me. But every time I left and came home, the climbers in my life, particularly the women I’d met in the climbing gym, would reach out and let me know how excited they were that I was home. How excited they were to see me. I really started to see how my own perception of myself was far from what others saw and interacted with.

This was validated in almost every international trip I took. Each place I found myself – Chile, Argentina, New Zealand, Australia – cultivated deep and meaningful relationships and small chosen families. I never questioned my value in these “families” and exuded confidence in myself and what I brought to the table. This allowed me to be vulnerable with them about my mental health and grief, but also allowed me to be loving, silly, and unashamedly myself.

As my year off ended, I made a commitment to myself to lean into female heavy spaces and into the nurture and support of the strong, inspirational women that were showing me every single time I was home that I was loved and missed, and that I was so much more than my grief was letting me see or how it was making me feel about myself.

I had previously been so overwhelmed by the idea of joining Womens Lead Club activities, my social anxiety and imposter syndrome rearing its head in the fiercest way, telling me that the women wouldn’t find me interesting or that they would think it wasn’t worth climbing with me because my lead head game was notoriously bad. My mind had me convinced that I had no business being a part of a club called Womens Lead Club if I panicked on 5.8’s outside and loved nothing more than top roping crag days where I’m nice and protected from above.

But as my year ended, I looked back on the international climbing I’d done with my chosen families – I’d bouldered in Argentina, sport climbed in NZ, and did my first multi-pitch swing lead in Australia. I reflected on the confidence and power I exuded in those spaces. I realized that the self judgement I had at home from having previously “failed” had created this narrative that I wasn’t capable at home of the same things I’d proven to be capable of literally across the world in a space where no one, including myself, had preconceived notions or judgments about me. If I could get out of my own way, I’d be free and I’d be so, so capable.

So I did the damn thing. I went to Women’s Lead and was welcomed with the most open of arms by women who are nothing short of amazing and empowering, but who also are so aligned with what I value and how I want to live and spend my life. It felt like coming home.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m still scared as all heck when leading, but in it I also feel understood and validated in a way I had not with previous climbing partners. These women are just excited to climb, regardless of what you’re coming in with. Since then, I’ve thrown myself into Women’s Lead Club, hosting a meetup, attending climber’s coffees, and participating in workshops and clinics. Women’s Lead Club has brought new meaning and excitement to my climbing.

My lead head game has also drastically improved, as I’ve continued to lean into my healing and into being loved and supported by those around me. Not only have I started to accept that I have value in my community spaces, but I have stopped people pleasing in my climbing and trying things I feel like I “should” do because someone says they know I can. Turns out listening to your body and where your head is at that day, instead of invalidating it because someone else says you’re fine, does wonders for personal growth!

I also finally have regular climbing dates with like-minded people (mostly women from the club!) who uplift, support, debrief, and meet me where I’m at on any given day. Because of this, I completed my goal for the season: successfully lead my first 5.10 outside, before the season even truly started!

Moral of the story: Community that you’re aligned with is imperative. Even more imperative is a strong sense of self and knowing your value, especially within that community. What a blessing to have finally figured out my place in this community, as well as my value/worth in it, and how good it feels to have removed the self judgement and doubt so that I can feel the joy I’d first seen was possible in the sport.

One of the most joyful things? Climbing has given me a space in which I finally feel safe enough to fail. For the first time in my life, failing is fun because it means I’m challenging myself and I get to grow! The joy is in the struggle and the projecting, and how lucky I am to get to persevere through hard tasks and come out the other side successful. Even more joyous? The overwhelming amount of gratitude and love I have for the women in the climbing community who continue to be the most badass rocks in this scary, emotional world. Thank you for holding space and care for me, but also for your companionship, silliness, inspiration, encouragement, and all of the laughs. It is because of all of you and your kindness, inclusivity, and love that I’ve made it out of a devastatingly dark era of feeling so utterly lost. You all are the brightest light and I love you.

Leave a Reply